The modern study of minimal superpermutations is largely traced back to Construction of small superpermutations and minimal injective superstrings by Daniel A. Ashlock and Jenett Tillotson. They provide the following definition of a superpermutation:

A superpermutation is a string over an alphabet $\mathcal{A}$ that contains every permutation of the elements of $\mathcal{A}$ as a contiguous substring.

Typically, we consider an alphabet $\mathcal{A} = \{ 1,2, \ldots, n \}$ for some $n \in \mathbb{Z}^+$. If we fix $n=k$ for some integer $k$, then a superpermutation over such an alphabet is called a superpermutation of $n=k$. Alternatively, this is often referred to as a superpermutation on $k$ symbols. For the sake of brevity, the alphabet $\mathcal{A}$ should be assumed to be $\{ 1,2, \ldots, n \}$ unless otherwise stated.

Motivating example

A trivial example of a superpermutation can be constructed as the concatenation of each permutation in an arbitrary order.

For example, consider $n=3$. Then, the permutations of $\mathcal{A} = \{ 1,2,3 \}$ are the following: $(1,2,3), (1, 3, 2), (2, 1, 3), (2, 3, 1), (3,1,2), (3,2,1)$. For the sake of brevity, I will denote ordered tuples as strings; that is, "123" instead of $(1,2,3)$. In addition, I will denote concatenation by $+$.

Then, $123 + 132 + 213 + 231 + 312 + 321 = 123132213231312321$, a superpermutation of $n=3$. For $n=k$, there will be $k!$ permutations of length $k$. Thus, this trivial superpermutation will have length $k\cdot k!$.

However, this construction has no overlaps and thus "saves" no characters. To illustrate this with a local example, consider that instead of concatenating $123 + 231 = 123231$, we can overlap 2 characters to get $1231$, which still contains $123$ and $231$ as substrings.

In fact, our naive construction is much longer than necessary. It is $3 \cdot 3! = 18$ characters long; however, the minimal superpermutation for $n=3$ is only 9 characters long: $123121321$.

Minimal superpermutation problem

The main focus of research regarding superpermutations is bounding and/or constructing minimal superpermutations for $n$.

As $n$ increases, it becomes exponentially more challenging to brute-force this problem. In fact, proven minimal superpermutations are only known for $n \le 5$. Moreover, it is now known that the classical formula $\sum_{k=1}^n k!$ is not optimal (disproved in 2014 by Robin Houston in Tackling the Minimal Superpermutation Problem).

As a result, the research has two main angles:

- Computational: attempting to narrow the search space in order to find a best-known (not proven minimal) superpermutation (in this context, "best" refers to shortest in length as a string)

- Theoretical: proving lower/upper bounds for the lengths of minimal superpermutations

For example, the example in the previous section constructively demonstrates that a minimal superpermutation of $n=k$ must have length no greater than $k \cdot k!$, since we know that we can construct a superpermutation of that length.

Note that a minimal superpermutation for $n=k$ is not unique (see Non-Uniqueness of Minimal Superpermutations by Nathaniel Johnston).

Current state of research

Here is a summary of the best-known superpermutations for $n \le 8$.

| n | best known length (upper bound) | best known lower bound | gap | proven minimal? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | yes |

| 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | yes |

| 3 | 9 | 9 | 0 | yes |

| 4 | 33 | 33 | 0 | yes |

| 5 | 153 | 153 | 0 | yes |

| 6 | 872 | 867 | 5 | no |

| 7 | 5906 | 5884 | 22 | no |

| 8 | 46205 | 46085 | 120 | no |

Sources:

- $n=6$ with length 872: Credit to Robin Houston (Tackling the Minimal Superpermutation Problem)

- $n=7$ with length 5906: Credit to Robin Houston and Greg Egan (Breaking News 2)

Strategies

Traveling salesman problem

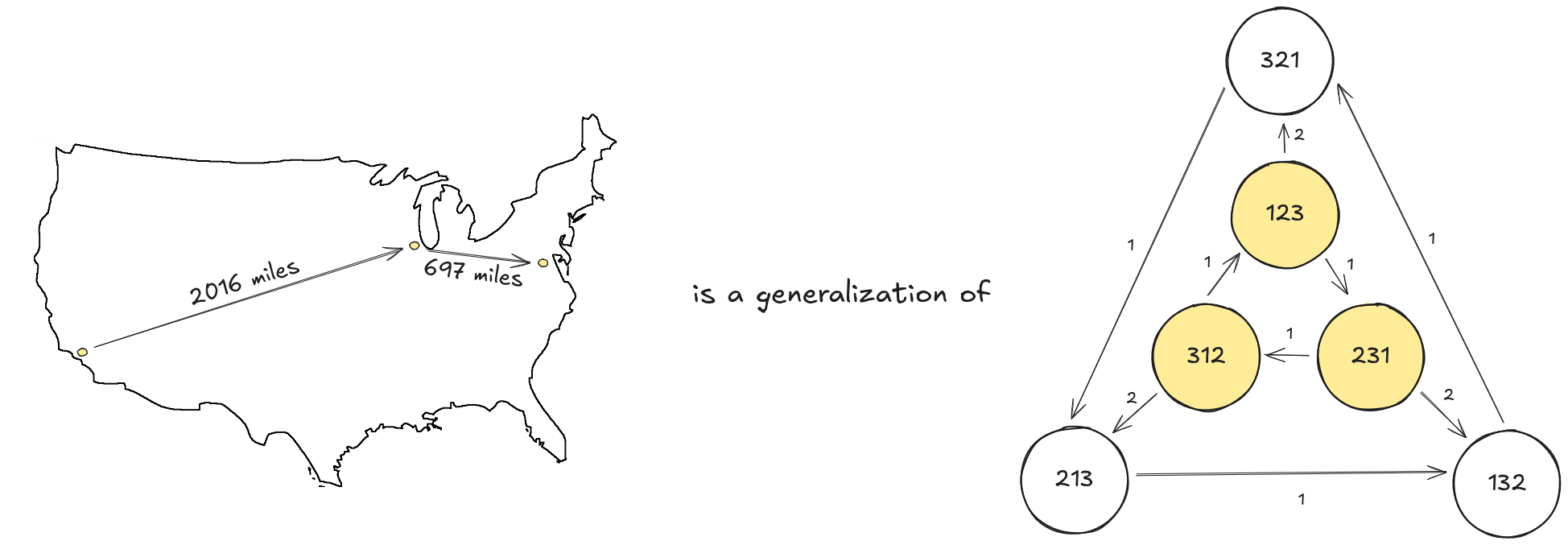

In the example, I hinted that we can treat the minimal superpermutation problem as an ordered arrangement of permutations. In fact, we can treat permutations as nodes and encode overlaps as ordered edge weights. Then, the minimal superpermutation problem can be expressed as the minimum-weight Hamiltonian path problem on this graph.

That is,

- Let $V = S_n$ (all $n!$ permutations as strings of length $n$)

- For $u, v \in V$, define the overlap $$\mathrm{ov}(u,v) = \max \{ k \in \{ 0, \ldots, n \} : \mathrm{suffix}_k (u) = \mathrm{prefix}_k (v) \}$$

- Define the directed edge weight from $u \to v$, where $u,v \in V$, as $$w(u,v) = n - \mathrm{ov}(u,v)$$

Then, any Hamiltonian path $u_1 \to u_2 \to \dots \to u_{n!}$ yields a superpermutation where we start with $u_1$ and append each $u_{i+1}$ using the maximal overlap with $u_i$.

Thus, the resulting superpermutation is constructed as $$u_1 + (\text{last } w(u_1, u_2) \text{ chars of }u_2) + \dots$$ which has a length of $$n + \sum_{i=1}^{n!-1} w(u_i, u_{i+1}).$$

In this way, the minimal superpermutation problem is equivalent to finding a minimum-weight Hamiltonian path in this complete asymmetric digraph. As a result, we can attempt to find a minimal superpermutation by adapting existing Asymmetric Traveling Salesman Problem (ATSP) solvers (note that many ATSP solvers are intended for cycles, rather than paths, but can be used by adding a dummy node with 0 weight edge to all nodes).

Rotation classes

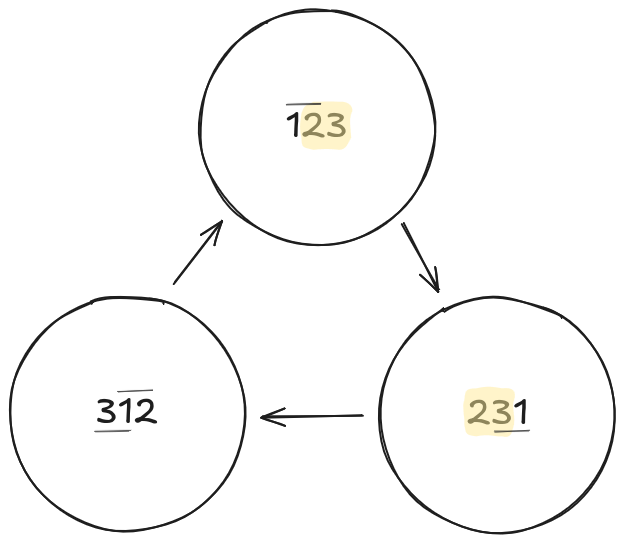

We can write all of the permutations of $n=3$ as the following:

$$\begin{aligned}123, 231, 312 \\ 132, 321, 213\end{aligned}$$

You may notice that permutations can be naturally grouped into $(n-1)!$ classes, each containing $n$ permutations. Within a class, we can "rotate" one character from the start of the string and place it at the end of the string to arrive at another permutation which, by definition, is in the same "rotation class". For example, see an example rotation class for $n=3$:

Note that if we path through adjacent members of a rotation class, then we can locally maximize the overlap. Now, we will formalize this idea.

Let's denote a permutation string with $a_1 a_2 \ldots a_n$ and define the rotation operator $\rho$ by $\rho(a_1 a_2 \ldots a_n) = a_2 \ldots a_n a_1$. Then, a rotation class is the orbit $\{ p, \rho(p), \rho^2(p), \ldots \}$.

In particular, in the overlap graph we see that $\rho^i(p) \to \rho^{i+1}(p)$ has an overlap of $n-1$ (that is, a weight of 1). Thus, we will likely desire to prioritize navigating through rotation classes.

However, the goal of global optimality is still hard; greedily following weight-1 edges can (and often will) force you into expensive transitions between classes. We need to intelligently pick some higher weight edges in order to achieve a globally minimal superpermutation.

Kernel Theory

The kernel approach to computing superpermutations is loosely documented in various online forums and (to my knowledge) has not been neatly compiled or published. However, it is the approach used by Greg Egan in the most recent record-breaking computation (a n=7 superpermutation with a length of 5906).

We begin by considering the problem as a constraint-propagation formulation. Instead of directly searching for a Hamiltonian path in the overlap graph, we will instead focus our attention on fixing permutations in the expected final superpermutation.

Recall that each permutation $p \in S_n$ is a string of length $n$. Let $N$ denote the total length of our final superpermutation.

We then introduce a position variable $$\mathrm{pos}(p) \in \{ 1,2,\ldots,N \}$$ which denotes the starting index of permutation $p$ in the final superpermutation. To the chagrin of computer scientists, I will be using 1-indexing.

From the overlap graph we constructed previously, we impose a constraint: for every ordered pair $u,v \in S_n$, if $\mathrm{pos}(u) \le \mathrm{pos}(v)$, then we require $$\mathrm{pos}(v) \ge \mathrm{pos}(u) + w(u,v)$$ with $w(u,v)$ as previously defined.

The core of this approach is the construction and expansion of a kernel. A kernel, for our purposes, is a partial assignment $$K = \{ (p_1, i_1), (p_2,i_2), \ldots (p_k, i_k) \}$$ where $p_j \in S_n$ and $i_1 < i_2 < \ldots < i_k$ with the meaning that $\mathrm{pos}(p_j) = i_j$.

Using Bellman-Ford-style relaxation, we can then compute $$\mathrm{pos}(p) \in [ L(p), U(p) ]$$ in a way that is consistent with all other constraints, for every permutation $p \in S_n$. That is, we are bounding each permutation to some interval. If for some $p$ we find $L(p) > U(p)$ then we say that our kernel failed to expand into a valid superpermutation. If $L(p) = U(p)$, then $p$ is forced to appear at a specific position.

Naturally, we define the forced count of kernel $K$ as $$\mathrm{forced\_count}(K) = |\{ p : L(p) = U(p) \}|.$$

In practice, a good kernel is one that has:

- no contradictions

- a small initial size $k$

- a large forced count, ideally close to $n!$

In the successful case, (possibly near) minimal superpermutations are found as the consequence of a small kernel rather than from exploring the entire TSP space.

Future

Unfortunately, there appears to be relatively little progress in the past several years despite the existence of many open questions.